Scrum is a buzzword, the virtue signal of choice for middle management in software organizations.

If your goal as a manager is to implement a system by which you:

- Speed up the appearance of progress

- Pay for twice the amount of people you need

- Gather approximate data based on meaningless metrics

Then Scrum is exactly what you’re looking for!

“Oh you had problems with Scrum at your last employer? Well, that’s not real Scrum.”

– your scrum master, who is not a true Scotsman

Problem #1 - Scrum Is Vague

It’s hard to criticize Scrum. The idea of “Scrum” in my mind is likely very different from the one you’re familiar with. This is by design, and it’s admitted to by the creators of Scrum. In the official Scrum Guide we find Scrum’s definition:

A framework within which people can address complex adaptive problems, while productively and creatively delivering products of the highest possible value.

I like to put it more tersely:

Scrum (noun) - 1. [software] Any good process that works good

Because the definition is so vague, the only things I’ll be able to critique in this article are the common Scrum practices that I’m familiar with. Hopefully, some of you lovely readers can relate.

Problem #2 - The “Sprint”

According to the official guide:

The heart of Scrum is a Sprint, a time-box of one month or less during which a “Done”, useable, and potentially releasable product Increment is created.

Sprints are useful like achievements in video games are useful; they make us feel warm and fuzzy inside. Motivation is a powerful tool, don’t misunderstand me. The problem is that those warm fuzzies are mostly for the sake of the management team. It makes leaders feel in control and informed. They know exactly what was done and when it was completed.

I’m not against management being informed… but at what cost?

Sprints require achievable short-term goals with a start and end date. To explore the potential problems, let’s pretend that I’m part of a team that does two-week sprints (because the duration must be consistent) and I’m assigned to build a microservice with an API. As an absolutely hypothetical example, let’s say I’m building a new achievements system for a gamified learning platform. We need new endpoints to:

- View achievements

- Unlock achievements

- Update the leaderboard based on achievements

- etc

As it turns out, we can’t user-test this system incrementally, because it’s not very useful to be able to view achievements without unlocking them. So, let’s also say that I estimate the whole task will take ~2 months if I work consistently on just this.

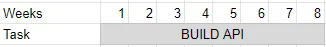

I need to break the API into pieces that can be completed in 2-week increments. We don’t plan super far ahead in Scrum (which is good, as requirements often change rapidly) so I just need to figure out what I can get done in my next sprint. I might be able to get some of the endpoints done quickly, but I do have other bugs to fix and I certainly don’t want to miss my goals, so I play it safe and estimate that in this first sprint I can complete two of the endpoints.

This creates artificial stopping points. Rather than just continuing with the API after the first two endpoints, I’m incentivized to stop. This doesn’t mean a good and honest developer actually would stop, but I’m incentivized by the system to stop. An API that could have been completed in 2 months could now take almost 4 months, but hey, at least management will have pretty burndown charts.

Problem #3 - The Scrum Master

From the official guide:

The Scrum Master is a servant-leader for the Scrum Team. The Scrum Master helps those outside the Scrum Team understand which of their interactions with the Scrum Team are helpful and which aren’t.

Depending on how the idea of the scrum master is implemented, it can be a bad idea or a worse one. Let’s just talk about the worst possible scenario where the scrum master is a non-technical, non-product people manager. A people person if you will.

In addition to all of their development work, the engineers are now interrupted frequently by the scrum master who is asking when the Java code for the React app will be done.

The very individual whose purpose is to stop the outside world from bothering the development team is the developer’s single biggest bother. In my experience, non-technical people should rarely be directly managing technical people, though there are always reasonable exceptions. Individual contributors should be able to go to their direct report for help and advice with engineering tasks, or at the very least they should expect them to understand their assignments.

Even if the scrum master is a lovable person who grasps the technical issues from a high level, Scrum Master isn’t a full-time job. If the scrum master never gets “down in the trenches” so to speak, I’m hesitant to believe they can stay busy in a meaningful way.

If you still feel the need for a scrum master, just let the lead developer for the team handle the job. They’re already at stand-up and likely have a better idea of what’s going on. You aren’t putting more on the development team’s plates, you’re likely lightening their load.

Problem #4 - Estimates

Within Scrum, estimates have a primary purpose - to figure out how much work the team can accomplish in a given sprint. If I were to grant that Sprints were a good idea (which I don’t) then the description of estimates in the official Scrum guide wouldn’t be a problem.

The problem is that estimates in practice are a bastardization of reality. The Scrum guide is vague on the topic so managers take matters into their own hands. With this in mind, I’m again going to criticize some common practices that I have seen regarding estimates.

Fibonacci and T-Shirt Sizes

Many super-hip organizations enjoy using the most confusing scales for estimates. They claim that this somehow makes estimating a faster and less stressful process. I remain woefully unconvinced.

Here’s a recap of the first day at a new company during our estimation meeting after hearing they used the dreaded “story points” system:

Me: “What’s the time scale we use for points?” Scrum master: “Fibonacci, where 8 points is the max because we defined it as the amount of work a developer can handle during a two-week sprint”.

I eventually learned the actual system.

- 1 point: 0 - 8 hours

- 2 points: 8 hours - 2.4 days

- 3 points: 2.4 days - 1 week

- 5 points: 1 week - 1.5 weeks

- 8 points: 2 weeks

The end goal of an estimate is to convert workload -> time. Why do we need to add an extra step of workload -> story points -> time? A simple estimate of “how many days?” would have been easier to think and reason about, while also providing more granularity.

A common objection to using such a barbarically simple system is:

We use fibonacci because its hard to imagine the difference between 7 and 8 days. No one can estimate that closely. Fibonacci sequences go up by ~60% at each step so you aren’t forced to get very close to your estimate.

To that, I propose base-2 exponentiation based on the scale you care about in the first place, time.

1, 2, 4, 8. Hours, days or weeks.

It seems we’ve solved the problem! Until another good-intentioned scrum master pipes up:

If estimates are grounded in measurable time then engineers will feel like they’ve screwed up if they miss their estimate.

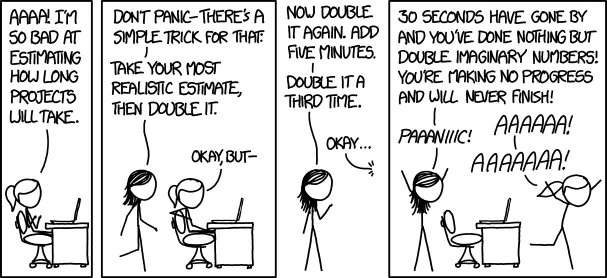

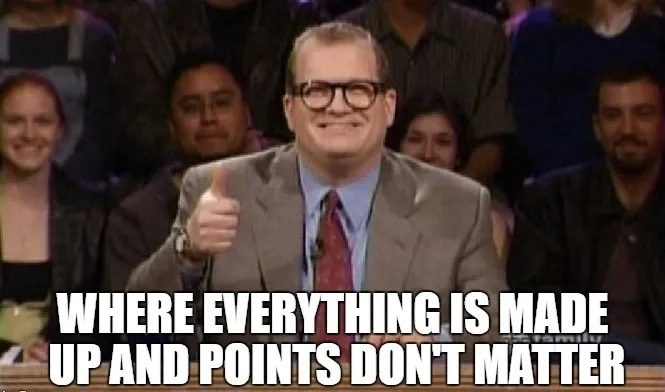

Good point, estimating is hard and we don’t want anyone to feel like they’re a bad engineer just because they aren’t the perfect estimator. That said, maybe instead of starting a game of “Whose Line Is It Anyway?”…

…we could set the reasonable expectation that estimates are just that, estimates.

Estimate - roughly calculate or judge the value, number, quantity, or extent of.

– oxford

If an estimate turns out to be bad it must be allowed to be re-estimated at no detriment to the estimator.

Final Note: Agile != Scrum

I’m generally a fan of agile methodologies and the Agile Manifesto. I’m not a fan of Scrum. In a later article (that I’ve now finished), I plan to go over my thoughts on what to do instead of Scrum while still running an “agile” organization.